In the first authentic document on the subject, the writings of Celsus, there is a complete teaching on the pathology and treatment of cataract. The preceding Hippocratic writings are silent on the subject, so that the Alexandrian school must have developed the teaching to the advanced level seen in Celsus. What exactly the Alexandrians did and where they found the basis for their studies, is a matter of conjecture. It is possible that the operation for depression was known in India since early days, but the evidence that it was known in Egypt and Babylon is more than doubtful. Celsus' account of cataract and its treatment was indeed the teaching that persisted till the 18th century with hardly any modification. The sudden eruption of a complete system of pathology and treatment from out of a historical void is but one of the many strange things in the history of cataract.Cataract as a name is of comparatively recent origin. It arose out of medieval Latin translations of Arabic writings and was a sort of shorthand term for expressing the pathology of the condition -- humour that flowed down into the eye. The older Latin name was suffusio and the Greek name, hypochyma, both having the same humoral implication; but these names were not revived to any extent when, with the Renaissance, men turned from translations from the Arabic to the original classical sources.

Suffusio with Celsus stood for that form of blindness which could be relieved, as opposed to glaucoma which was a form of incurable blindness. In suffusion corrupt, inspissated humour collected in the locus vacuus between the pupil and the lens, thus obstructing the visual spirits. By clearing this empty space vision could be restored. The obstruction caused by the suffusio could be removed in the early stages by medicinal treatment, but when fully formed only by operative displacement into a part of the eye other than the front of the lens. The operation involved entering a sharp, but not too slender needle into the eye and when resistance was felt on touching the suffusio, this structure was gently worked down away from the pupil. If it did not stay down the suffusio had to be broken up in pieces and these fragments were then depressed. Celsus gives a detailed account of the pre- and post-operative treatment. Incidentally, a later Roman writer attributed the development of this operation to the casual observation that vision was restored to a goat, blind from cataract, when it ran its eye on to a thorn.

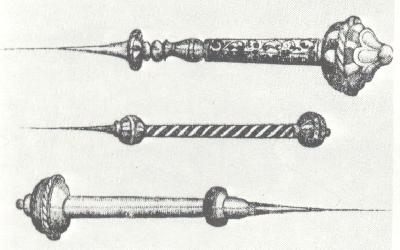

A set of couching needles.The conception of cataract as inspissated humour in front of the lens persisted with Galen, in whose anatomy there was no locus vacuus. During Arabian times the conception became even more firmly rooted and the central position of the lens in the anatomy of Vesalius is evidence of the firmness with which the belief was held. The epoch-making work of Kepler and his forerunners in dethroning the lens from its position as the essential organ of vision had no immediate result on the teaching as to the nature of cataract. At about the middle of the 17th century more than one observer began to question whether cataract was not indeed an affection of the lens, but the rooted belief that glaucoma was due to drying of the lens was a great obstacle to the resolution of these questions and doubts. Characteristic of these doubts is the observation by Dechales that the reason why strong convex lenses are needed by patients operated on for cataract must be that the secretion destroys the spherical shape of the lens. By actual demonstration of an opaque lens in cataract, Rolfinck in 1656 crystallized a considerable amount of discussion and teaching by both physicists and oculists. About thirty years later Maître-Jan noted that it was not a thin membrane but a thick rounded body that was displaced when on two occasions he chanced to displace the cataract into the anterior chamber instead of into the vitreous. e further had the opportunity of examining the eyes of patients whose cataracts he had couched and found that it was the lens itself that was displaced. He concluded that cataract and glaucoma were indeed one and the same disease, but the one was curable and the other not.

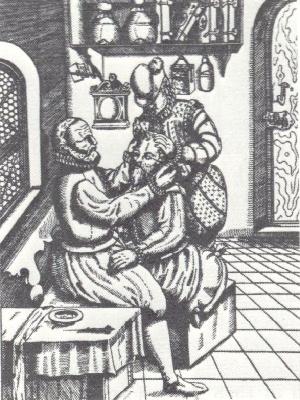

Couching (depression of the lens) in the late

16th century.These observations passed unnoted. When Brisseau, a young man at the beginning of his career, rediscovered in 1705 all this for himself, his friend and teacher Duverney advised him against publication, if he did not wish to jeopardize his future. However, his findings went forward to the Académie Royale des Sciences, through the intermediary of a member of it, only to be told that the views expounded therein had made but little impression. Brisseau had nevertheless succeeded in raising a controversy -- a thing in which his predecessors had failed. Maître-Jan came forward with his own proofs as the truth of the new conception, and Brisseau himself advanced further proof. De la Hire and Mery were prominent in the opposition, whilst Petit supported Brisseau. However, in searching for conclusive evidence against Brisseau, Mery convinced himself of the error of his own views and came out in the Academy strongly in favour of the new teaching. Indeed in the Academy the battle was soon won, but for years the repercussions distracted the rest of Europe. Boerhaave, Morgagni, Valsalva and Cheselden were amongst the supporters of the new school, whilst prominent amongst distinguished opponents was that brilliant charlatan, Thomas Woolhouse.

The acceptance of the new pathology precipitated acutely the problem of glaucoma, for glaucoma was acutely the problem of glaucoma, for glaucoma was held to be a disease of the lens. It also forced attention to such conditions as obscured the pupil and were not cataract. It thus involved a new pathology as to the causes and treatment of blindness.

Hardly had the furore caused by this controversy died down before another storm broke which was destined to last throughout the second half of the 18th century and to be prolonged well into the 19th. Brisseau did in 1743b. Five years later Daviel published his account of extraction of the lens.

The radical treatment of cataract as practised today is essentially the method of Daviel. But previous attempts at radical treatment were not wanting. Indeed there are puzzling passages in the older writers which would lead one to believe that extraction had some transient vogue in ancient days. There is the bleak passage in Galen which speaks of some who, instead of displacing the cataract to a site where it is less troublesome than in front of the lens, "have attempted to extract it, as I shall show in the book dealing with operation." This book is lost and the later Greek writers do not refer to the operation. Roundabout information comes from Arabian sources. Salah-ad-din reports Razi as saying that according to Antyllos some divide the lower part of the pupil and extract the cataract, the procedure being possible only with thin cataracts, as with thick cataracts the humour (aqueous) also escapes.

These references to extraction in all probability implied some form of evacuation. A much more significant attempt at the radical removal fo the cataract is due to the Arabian, Ammar, who elaborated the operation of suction. The introduction of a glass tube through a corneal incision for removing cataract is also referred to in the passage "according to Antyllos." Arabian practitioners before Ammar certainly practised it, but it was left to Ammar to devise a hollow needle introduced through the sclera, thus avoiding an incision into the anterior chamber and consequent loss of aqueous, which was regarded as a calamity. Western Caliphate and in Christendom. In the East it found a readier reception. In Western Europe the operation had to be rediscovered during the last century.

Surgical treatment of cataract at the time of Daviel was therefore confined to depression. Breaking up the lens piecemeal, to induce depression in such cases where the lens would not stay down, was a course adopted only as a matter of necessity. Daviel's cataract operation was therefore as marked an innovation in treatment as the work of Maître-Jan and Brisseau had been in pathology.

Before Daviel the possibility of extraction was "in the air." When Mery recognized the truth of Brisseau's work he also saw that it might be possible to extract the opaque lens by an incision into the eye. The lens was actually extracted by St. Yves in 1722, but it was extraction of a lens which had become displaced into the anterior chamber during an attempt at depression. Piecemeal removal of a broken-up lens, particles of which had floated into the anterior chamber, was also carried out by Petit; and it was a similar unplanned emergency procedure that started Daviel on his planned extraction. What had been forced on him by accident and, incidentally, had proved utterly unsuccessful, he repeated deliberately in a second case -- deliberately making an opening through the cornea and removing the lens piecemeal. Actual extraction of the lens en masse was forced on him in a case in which he failed to couch the cataract. He then "decided to open the lower portion of the cornea in order to get my needle the more effectively into the posterior chamber". A year later (1748) he published his account, but it was some years before he finally decided in favour of extraction to the exclusion of depression.

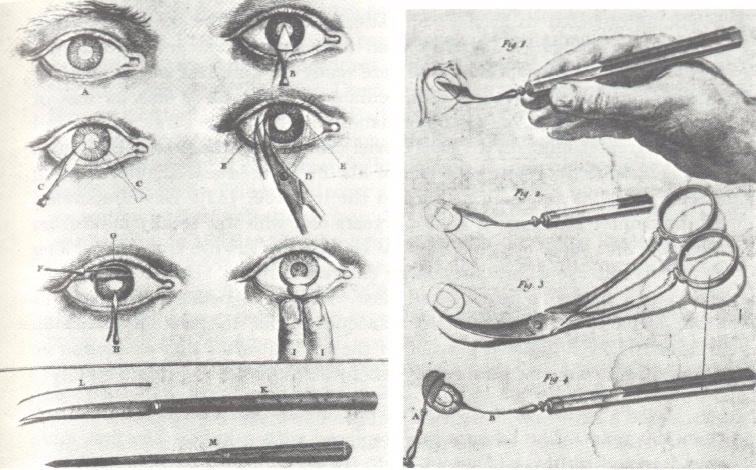

Daviel's operation consisted of a corneal incision near the limbus below, made by puncture with a sharp curved needle, enlargement of this puncture to the right and left with a blunt curved needle, and completion of the incision to the right and left with curved, convex scissors; the incision having been made, a spatula was introduced into the eye, and while it held the cornea away from the lens, the sharp needle was used for opening the capsule; the spatula was next passed between the iris and lens to free any adhesions; gentle pressure to dislodge the cataract completed the operation (see picture below).

Daviel's method of cataract extractionThe operation was taken up enthusiastically -- but only for a brief space. Everywhere influential support for the older operation became consolidated, and new methods for couching were developed. During the hundred years in which Daviel's operation was on trial many modifications of an ephemeral vogue were introduced. The complicated incision practised by Daviel soon enough gave way to a single incision by a knife, special patterns being introduced by almost every operator. At an early stage incision at the upper limbus was proposed, but this gave way to a modified incision lower down. Other modifications aimed at different varieties of corneal incision, the variations ranging from semi-circular to triangular. To obviate suppuration and promote better healing scleral incisions were advocated. This was partly the underlying principle of von Graefe's linear incision, an operation that was soon given up because of cyclitis and sympathetic ophthalmia which so frequently followed. Mooren's preliminary iridectomy, introduced in 1864, constitutes the one generally accepted radical modification that Daviel's operation has undergone during its career of nearly two centuries.